Friend

Friend

Chinese Martial Arts

Chinese martial arts, which are called kung fu (Pinyin: gong fu) or wushu, are a number of fighting styles that have developed over the centuries in China. These fighting styles are often classified according to common traits, identified as “families” (jia), “sects” (pài) or “schools” (mén) of martial arts. Examples of such traits include physical exercises involving animal mimicry, or training methods inspired by Chinese philosophies, religions and legends. Styles that focus on qi manipulation are called internal (nèijiaquán), while others that concentrate on improving muscle and cardiovascular fitness are called “external” (wàijiaquán). Geographical association, as in northern (beiquán) and “southern” (nánquán), is another popular classification method.

Terminology

Kung fu and wushu are loanwords from Chinese that, in English, are used to refer to Chinese martial arts. However, the Chinese terms kung fu and wushu; (Cantonese: móuh-seuht) have distinct meanings. The Chinese equivalent of the term “Chinese martial arts” would be Zhongguo wushu (Pinyin: zhongguó wushù).

In Chinese, the term kung fu refers to any skill that is acquired through learning or practice. It is a compound word composed of the words (gong) meaning “work”, “achievement”, or “merit”, and (fu) which is a particle or nominal suffix with diverse meanings.

Wushù literally means “martial art”. It is formed from the two words (wu), meaning “martial” or “military” and (shù), which translates into “discipline”, “skill” or “method.” The term wushu has also become the name for the modern sport of wushu, an exhibition and full-contact sport of bare-handed and weapons forms, adapted and judged to a set of aesthetic criteria for points developed since 1949 in the People’s Republic of China.

Quan fa is another Chinese term for Chinese martial arts. It means “fist principles” or “the law of the fist” (quan means “boxing” or “fist” [literally, curled hand], and fa means “law”, “way” or “study”). The name of the Japanese martial art Kenpo is represented by the same characters.

Legendary Origins

According to legend, Chinese martial arts originated during the semi-mythical Xia Dynasty more than 4,000 years ago. It is said the Yellow Emperor Huangdi (legendary date of ascension 2698 BCE) introduced the earliest fighting systems to China. The Yellow Emperor is described as a famous general who, before becoming China’s leader, wrote lengthy treatises on medicine, astrology and the martial arts. One of his main opponents was Chi You who was credited as the creator of jiao di, a forerunner to the modern art of Chinese Wrestling.

Luc Paquin

About Oliver Sacks

Biography

Oliver Sacks, MD, FRCP

Oliver Sacks was born in 1933 in London, England into a family of physicians and scientists (his mother was a surgeon and his father a general practitioner). He earned his medical degree at Oxford University (Queen’s College), and did residencies and fellowship work at Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco and at UCLA. Since 1965, he has lived in New York, where he is a practicing neurologist.

From 2007 to 2012, he served as a Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, and he was also designated the university’s first Columbia University Artist. Dr. Sacks is currently a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine, where he practices as part of the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center. He is also a visiting professor at the University of Warwick.

In 1966 Dr. Sacks began working as a consulting neurologist for Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, a chronic care hospital where he encountered an extraordinary group of patients, many of whom had spent decades in strange, frozen states, like human statues, unable to initiate movement. He recognized these patients as survivors of the great pandemic of sleepy sickness that had swept the world from 1916 to 1927, and treated them with a then-experimental drug, L-dopa, which enabled them to come back to life. They became the subjects of his bookAwakenings, which later inspired a play by Harold Pinter (“A Kind of Alaska”) and the Oscar-nominated feature film (“Awakenings”) with Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

Sacks is perhaps best known for his collections of case histories from the far borderlands of neurological experience, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and An Anthropologist on Mars, in which he describes patients struggling to live with conditions ranging from Tourette’s syndrome to autism, parkinsonism, musical hallucination, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, retardation, and Alzheimer’s disease.

He has investigated the world of Deaf people and sign language in Seeing Voices, and a rare community of colorblind people in The Island of the Colorblind. He has written about his experiences as a doctor in Migraine and as a patient in A Leg to Stand On. His autobiographicalUncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood was published in 2001, and his most recent books are Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (2007), The Mind’s Eye (2010), and Hallucinations (2012).

Sacks’s work, which has been supported by the Guggenheim Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, regularly appears in the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, as well as various medical journals. The New York Times has referred to Dr. Sacks as “the poet laureate of medicine”, and in 2002 he was awarded the Lewis Thomas Prize by Rockefeller University, which recognizes the scientist as poet. He is an honorary fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and holds honorary degrees from many universities, including Oxford, the Karolinska Institute, Georgetown, Bard, Gallaudet, Tufts, and the Catholic University of Peru.

Oliver Sacks

Norma

Kung fu/Kungfu or Gung fu/Gongfu is a Chinese term referring to any study, learning, or practice that requires patience, energy, and time to complete, often used in the West to refer to Chinese martial arts. It is only in the late twentieth century, that this term was used in relation to Chinese martial arts by the Chinese community. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the term “kung-fu” as “a primarily unarmed Chinese martial art resembling karate.” This illustrates how the meaning of this term has been changed in English. The origin of this change can be attributed to the misunderstanding or mistranslation of the term through movie subtitles or dubbing.

In its original meaning, kung fu can refer to any skill achieved through hard work and practice, not necessarily martial arts. The Chinese literal equivalent of “Chinese martial art” would be zhongguó wushù.

In Chinese, gongfu is a compound of two words, combining (gong) meaning “work”, “achievement”, or “merit”, and (fu) which is alternately treated as being a word for “man” or as a particle or nominal suffix with diverse meanings (the same character is used to write both). A literal rendering of the first interpretation would be “achievement of man”, while the second is often described as “work and time/effort”. Its connotation is that of an accomplishment arrived at by great effort of time and energy. In Mandarin, when two “first tone” words such as gong and fu are combined, the second word often takes a neutral tone, in this case forming gongfu.

Originally, to practice kung fu did not just mean to practice Chinese martial arts. Instead, it referred to the process of one’s training – the strengthening of the body and the mind, the learning and the perfection of one’s skills – rather than to what was being trained. It refers to excellence achieved through long practice in any endeavor. This meaning can be traced to classical writings, especially those of Neo-Confucianism, which emphasize the importance of effort in education.

However, the phrase (kung fu wu shu) does exist in Chinese and could be (loosely) translated as “the skills of the martial arts”.

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts and Spirituality

Your spirit shows itself when you stop putting things off. Without fearing what is about to happen, simply being in the moment, naturally. We’ve all had the experience of getting up in front of a crowd to give a talk or present something. Maybe we allowed ourselves to be intimidated by the crowd, kind of shinking inside of ourselves. Not being the best showman we could be. We didn’t have the “showman’s spirit”. We didn’t allow ourselves to do as well as we could. We just didn’t have enough “spirit” to make the best presentation we could. Spiritual practice’s are those that teach you to except what is happening and who you are in order to let yourself, your spirit, shine through. When you are coming from a spiritual place you are acting without fear, worry, doubt, or any kind of dependence on what will happen next, you are simply being you, right now.

Understanding spirit, and spirituality in this way; its connection to the martial arts is undeniable. Martial situations are ones that require strong spirit. If your spirit isn’t strong you’ll never get through extreme difficulty’s. If your spirit isn’t strong it’s impossible to come through tragedy and not be a victim. And for these very reasons Martial practices make wonderful training grounds for the spirit. Lending the martial arts to being a wonderful spiritual practice. Most religions and non-martial spiritual schools have to add practices in order to train the spirit. Challenges and difficulties must be faced in order to strengthen your spirit. Non-martial spiritual traditions add things like: abstinence, fasting, tithing, worship, routine, strict moralities etc. in order to challenge their practitioners. Martial practices however have a built in set of challenges: fighting, physical fatigue, and habitual practice are the necessities of a martial method. Practices like these make simple sense in the martial arts. You never have to ask, “why do I need to be in good physical shape”, “Why do I actually need to test my skills against someone”, or “why do I need to train so much”. The reasons are clear, if you want to be good, you’ll have to do these things. You must use your spirit to get through these rigors, this trains the spirit. It’s hard to hide behind lies, and clever excuses, if you’re not training hard, it’s clear that your spirit is not in the practice.

The great thing about spiritual training is that it will naturally start to spill over into the rest of your life. When you honestly take on training in the martial arts, you take on a spiritual practice that makes you a stronger person. Dealing with things directly and honestly starts to be much less challenging. When you willingly participate in physical conflict, dealing with the grumpy bus boy suddenly isn’t a big deal. When you force yourself to joyfully except vigorous exercise, doing yard work is no problem. A strong spirit is useful in all facets of life, and will do far more for you then make you a good fighter.

You must pay attention to this. You must actually make Spirituality a practice. If you fight simply because you’re mad, or “want too” you’re not training your spirit. You are simply giving in to an indulgence. If you show up at your Dojo and simply go through the motions, you’re not training your spirit. If you get excited and feed your ego every time you pin someone, or give them a big throw, complaining every time you are thrown, you’re not training your spirit. You must stay ever mindful, taking care in all of your training. This will make your practice something phenomenal. Something that will strengthen your spirit, and increase your martial ability. Eventually there will be no more “spirit of giving”, or “fighting spirit”, because everything you do will involve spirit. Giving you something we could all use a little more of in our lives, Joy.

Christopher Hein

Luc Paquin

About Oliver Sacks

Oliver Sacks, M.D. is a physician, a best-selling author, and a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine. The New York Times has referred to him as “the poet laureate of medicine”.

He is best known for his collections of neurological case histories, including The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain and An Anthropologist on Mars. Awakenings, his book about a group of patients who had survived the great encephalitis lethargica epidemic of the early twentieth century, inspired the 1990 Academy Award-nominated feature film starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

Dr. Sacks is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books.

Oliver Sacks

Norma

Martial Arts and Spirituality

Martial arts and spirituality. What does that even mean? This is a question almost all of us ask. But few of us ever get any real answers. Some say it’s mixing religions such as Christianity or Islam with martial arts. Some think it’s dressing up in flowing clothes, spouting koans, and seeming esoteric. Some say it’s simply, “a bunch of crap”.

However I believe It isn’t any of these things.

To understand the relationship between Martial arts and spiritually, you must first understand what each of them are on their own. Most of us pretty much understand, or at least have a clear concept of what the martial arts are. I’ll define it here as the study of physical conflict. But there are lots of reasonable definitions. Most of us have spent enough time with the martial arts, that we have a pretty clear definition, at least for ourselves. It’s spirituality that many of us have a hard time with.

To many, spirituality is simply going to church and reading the bible. While these things are spiritual things, they are part of a religion, and not the spirituality itself. A religion is a school of spirituality. The main goal of these schools is to put people in touch with their spirituality. The practices of a religion (prayer, bible reading, church services, worship etc.) are designed to put you in touch with your spirituality, but they are not the spirituality itself. By adding the practices of your religion to your martial arts, you are not working with spirituality, you are simply adding more practices. Which most martial arts systems already have more then enough of. Religion’s are to spirituality as Martial arts are to fighting. They are schools that point to a thing, but not the thing itself. Mixing the practices of a religion into your martial arts doesn’t train your spirit.

The trappings of spirituality are not the spirit. While different physical objects can help evoke your spirit, they are not the spirit itself. Wearing a Zen masters robes certainly does not make you a Zen master. Reciting words and incantations that you don’t understand does not make you a spiritual person. Seeming aloof and exotic to other people doesn’t do a thing for your spirituality either. It starts with you.Your spirit is at the very core of what you are. So how could you find it in things outside of yourself?

Because of our tendency to confuse spirit with practices and trappings, many of us come to the conclusion that spirituality is just a bunch of nonsense and doesn’t exist at all. However if you look to the normal instead of the extreme we can readily see examples of spirit in our daily lives. Some common indications of spirit are: “the spirit of giving”, “the Christmas spirit”, “Fighting spirit”, etc. We all understand these examples, and accept them with little doubt as to their existence. The reason is because we’ve all experienced them or seen them in our lives. We don’t think of these things as being different or special, they are just part of life.

Spirit is complete manifestation of true self. Let’s look at it in terms of “the spirit of giving”. Most all of us have been over taken by this at one time or another, and are quite familiar with it. We know that it is a feeling of joyful giving. It can seem almost addictive. You just start giving things, maybe even expensive or important things, to people you care about. Every part of you wants to give. Once you surrender to your spirit, everything seems to come together for you. The same can be said of “fighting spirit”. When someone has a strong fighting spirit, they except the fact that they are in the midst of struggle. In fact they happily engage, excepting what is happening, exhibiting a kind of joy. They do this even in the face of agony or defeat.

Christopher Hein

Luc Paquin

Joseph A. Adler

Penetrating the Classic of Change (Tongshu)

The Tongshu, in forty sections, focuses on the Sage as the model of humanity. Here Zhou Dunyi defines Sagehood in terms of “authenticity” (cheng), a term found prominently in the classical Confucian text, The Mean (Zhongyong). To be authentic is to be true to the innate goodness of one’s nature; to actualize one’s moral potential. Zhou defines authenticity in cosmological terms taken from the appendices to the Classic of Change (Yijing). In this way he uses the concept of authenticity to link cosmology and Confucian ethics. There is significant overlap between the Tongshu and theTaijitu shuo (above), especially in their discussions of activity and stillness as the basic expressions of yang and yin. But the Tongshu is less metaphysical; the emphasis here is on the moral psychology of the Sage.

1. Being authentic (cheng)

- Being authentic is the foundation of the Sage. “Great indeed is the originating [power] of Qian! The myriad things rely on it for their beginnings.” It is the source of being authentic. “The way of Qian is transformation, with each [thing] receiving its correct nature and endowment.” In this way authenticity is established. Being pure and flawless, it is perfectly good. Thus: “The alternation of yin and yang is called the Way. That which issues from it is good. That which fulfills it is human nature.” “Origination and development” are the penetration of authenticity; “adaptation and correctness” are the recovery of authenticity. Great indeed is change (yi)! It is the source of human nature and endowment.

2. Being authentic (cheng)

- Being a Sage is nothing more than being authentic. Being authentic is the foundation of the Five Constant [Virtues] and the source of the Hundred Practices. It is imperceptible when [one is] still, and perceptible when [one is] active; perfectly correct [in stillness] and clearly pervading [in activity]. When the Five Constants and Hundred Practices are not authentic, they are wrong; blocked by depravity and confusion.

- Therefore one who is authentic has no [need for] undertakings (shi). It is perfectly easy, yet difficult to practice; when one is determined and precise, there is no difficulty with it. Therefore [Confucius said], “If in one day one could subdue the self and return to ritual decorum, then all under Heaven would recover their humanity.”

3. Authenticity, Incipience, and Virtue (cheng ji de)

- In being authentic there is no deliberate action (wuwei). In incipience (ji) there is good and evil. As for the [Five Constant] Virtues, loving is called humaneness (ren), being right is called appropriateness (yi), being principled (li) is called ritual decorum (li), being penetrating is called wisdom (zhi), and preserving is called trustworthiness (hsin). One who is by nature like this, at ease like this, is called a Sage. One who recovers it and holds onto it is called a Worthy. One whose subtle signs of expression are imperceptible, and whose fullness is inexhaustible, is called Spiritual (shen).

4. Sagehood (sheng)

- That which is “completely silent and inactive” is authenticity. That which “penetrates when stimulated” is spirit (shen). That which is active but not yet formed, between existing and not existing, is incipient. Authenticity is of the essence (jing), and therefore clear. Spirit is responsive, and therefore mysterious. Incipience is subtle, and therefore obscure. One who is authentic, spiritual, and incipient is called a Sage.

5. Activity and Stillness (dong jing)

- Activity as the absence of stillness and stillness as the absence of activity characterize things (wu). Activity that is not [empirically] active and stillness that is not [empirically] still characterize spirit (shen). Being active and yet not active, still and yet not still, does not mean that [spirit] is neither active nor still. For while things do not [inter-]penetrate (tong), spirit subtly [penetrates/pervades] the myriad things.

- The yin of water is based in yang; the yang of fire is based in yin. The Five Phases are yin and yang; yin and yang are the Supreme Polarity. The Four Seasons revolve; the myriad things end and begin [again]. How undifferentiated! How extensive! And how inexhaustible!

6. Learning to be a Sage (sheng xue)

- [Someone asked:] “Can Sagehood be learned?” Reply: It can. “Are there essentials (yao)?” Reply: There are. “I beg to hear them.” Reply: To be unified (yi) is essential. To be unified is to have no desire. Without desire one is vacuous when still and direct in activity. Being vacuous when still, one will be clear (ming); being clear one will be penetrating (tong). Being direct in activity one will be impartial (gong); being impartial one will be all-embracing (pu). Being clear and penetrating, impartial and all-embracing, one is almost [a Sage].

Luc Paquin

Joseph A. Adler

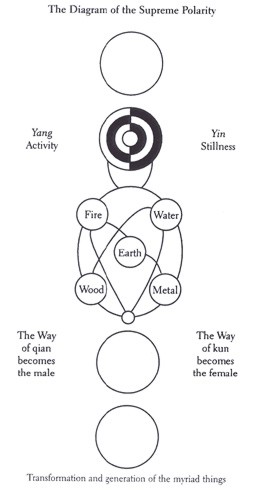

“Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taiji tu)

“Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taijitu shuo)

- Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)! The Supreme Polarity in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established.

- The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.

- The reality of the Non-polar and the essence of the Two [Modes] and Five [Phases] mysteriously combine and coalesce. “The Way of Qian becomes the male; the Way of Kun becomes the female;” the two qi stimulate each other, transforming and generating the myriad things. The myriad things generate and regenerate, alternating and transforming without end.

- Only humans receive the finest and most spiritually efficacious [qi]. Once formed, they are born; when spirit (shen) is manifested, they have intelligence; when their five-fold natures are stimulated into activity, good and evil are distinguished and the myriad affairs ensue.

- The Sage settles these [affairs] with centrality, correctness, humaneness and rightness (the Way of the Sage is simply humaneness, rightness, centrality and correctness) and emphasizes stillness. (Without desire, [he is] therefore still.) In so doing he establishes the ultimate of humanity. Thus the Sage’s “virtue equals that of Heaven and Earth; his clarity equals that of the sun and moon; his timeliness equals that of the four seasons; his good fortune and bad fortune equal those of ghosts and spirits.” The superior person cultivates these and has good fortune. The inferior person rejects these and has bad fortune.

- Therefore [the Classic of Change says], “Establishing the Way of Heaven, [the Sages] speak of yin and yang; establishing the Way of Earth they speak of yielding and firm [hexagram lines]; establishing the Way of Humanity they speak of humaneness and rightness.” It also says, “[The Sage] investigates beginnings and follows them to their ends; therefore he understands death and birth.” Great indeed is [the Classic of] Change! Herein lies its perfection.

Luc Paquin

Dr. Oliver Sacks wrote and told many stories over the years about his patients’ struggles with disease and their feats in the face of extraordinary challenge. In one of them, he narrates how he used to greet aphasia patients by singing “Happy Birthday” to them, irrespective of whether it was their birthday or not. He did this because everyone knew the words of this song, and often even people who had lost their ability to speak could sing along parts of it. It was his kind way of letting a person with aphasia join in.

Today is the 82nd birthday of Dr. Sacks – a luminous mind, a celebrated writer, and a treasured board member of the National Aphasia Association. As many of you may have already heard, Dr. Sacks recently shared with the public that he has terminal cancer. The news has saddened many hearts, including ours here at the NAA. But today, on this special birthday, we wanted to celebrate with Dr. Sacks the years he has spent bringing to us the magic of science and medicine through his fascinating writing and language. And we wanted to thank him for his extraordinary kindness towards persons with aphasia. We have selected a few excerpts and videos where Dr. Sacks talks about Aphasia and his personal encounters with people who suffer from this devastating communication deficit.

Maybe the best place to start is an excerpt from The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, one of the most beloved books from Oliver Sacks, a collection of clinical tales about patients with neurological disorders. The book includes accounts about aphasia as well. One of those tales relates the story of patients with the severest receptive or global aphasia who had gathered to watch the President speaking. It begins like this:

- What was going on? A roar of laughter from the aphasia ward, just as the President’s speech was coming on, and they had all been so eager to hear the President speaking…

Dr. Sacks has had many encouraging words for people with aphasia, even those who have had the hardest of luck.

- I think that even in the most severely affected patients, something can be done. If not by way of recovering their language, by way of making life more tolerable and more fun.

In a 2009 interview with Harper’s Magazine about his book Musicophilia, Dr. Sacks answers questions about music therapy, among other things. He shares his experience with an aphasia patient for whom this type of therapy proved life changing.

- One sixty-seven-year-old man, aphasic for eighteen months – he could only produce meaningless grunts and had received three months of speech therapy without effect – started to produce words two days after beginning melodic intonation therapy; in two weeks, he had an effective vocabulary of a hundred words, and at six weeks, he could carry on “short, meaningful conversation”s.

In this video Oliver Sacks talks about a patient, a woman called Patricia, who had had a stroke that resulted in aphasia. Dr. Sacks recounts how her extraordinary will and ability to find a way around her communication deficits has inspired him to write about her.

Besides being touching stories about patients, these accounts also show the interest Dr. Sacks took in his patients, their problems, and the way disease affected their lives.

Happy Birthday, Dr. Sacks!

Norma

Joseph A. Adler

Diagram of the Supreme Polarity (Taiji tu)

Zhou’s best-known contribution to the Neo-Confucian tradition was his brief “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” and the Diagram itself. The text has engendered controversy and debate ever since the twelfth century, when Zhu Xi and Lü Zuqian (1137-1181) placed it at the head of their Neo-Confucian anthology, Reflections on Things at Hand (Jinsilu), in 1175. It was controversial from a sectarian Confucian standpoint because the diagram explained by the text was attributed to a prominent Daoist master, Chen Tuan (Chen Xiyi, 906-989), and because the key terms of the text had well-known Daoist origins. Scholars to the present day have attempted to interpret what Zhou Dunyi meant by them.

The two key terms, which appear in the opening line of the Explanation, are wuji and taiji, translated here as “Non-Polar” and “Supreme Polarity.” Wuji had been used in the classical Daoist texts, Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Liezi. Wu is a negation, roughly equivalent to “there is not;” ji is literally the ridgepole of a peaked roof, and usually means “limit” or “ultimate.” So in these early texts wuji means “the unlimited,” or “the infinite.” But in later Daoist texts it came to denote a state of primordial chaos, prior to the differentiation of yin and yang, and sometimes equivalent to dao.

Taiji was found in several classical texts, mostly but not exclusively Daoist. For the Song Neo-Confucians, the locus classicus of taiji was the Appended Remarks (Xici), or Great Treatise (Dazhuan), one of the appendices of the Classic of Change (Yijing): “In change there is the Supreme Polarity, which generates the Two Modes [yin and yang]”. Taiji here is a generative principle of bipolarity.

But the term was much more prominent and nuanced in Daoism than in Confucianism. Taiji was the name of one of the Daoist heavens, and thus was prefixed to the names of many Daoist immortals, or divinities, and to the titles of the texts attributed to them. It was sometimes identified with Taiyi, the Supreme One (a Daoist divinity), and with the pole star of the Northern Dipper. It carried connotations of a turning point in a cycle, an end point before a reversal, and a pivot between bipolar processes. It became a standard part of Daoist cosmogonic schemes, where it usually denoted a stage of chaos later than wuji, a stage or state in which yin and yang have differentiated but have not yet become manifest. It thus represented a “complex unity,” or the unity of potential multiplicity. In the form of Daoist meditation known as neidan, or physiological alchemy, it represented the energetic potential to reverse the normal process of aging by cultivating within one’s body the spark of the primordial qi (psycho-physical substance), thereby “returning” to the primordial, creative state of chaos from which the cosmos evolved. Chen Tuan’s Taiji Diagram, when read from the bottom upwards, is thought to have been originally a schematic representation of this process of “returning to wuji”, the “Non-Polar,” undifferentiated state.

Zhou Dunyi ignored the bottom-up reading of the Diagram, leaving one or two of its elements unexplained. Focusing on the top-down differentiation of the cosmos from the primordial unity to the “myriad things,” he departed from a Daoist interpretation by singling out the human being as the highest manifestation of cosmic creativity, thereby giving the Diagram a distinctly Confucian meaning. The enigmatic opening line of his Explanation suggests that the Supreme Polarity, the ultimate principle of differentiation, is itself fundamentally undifferentiated (this is stated explicitly a few sentences later). Similarly, activity and stillness, the first manifestations of polarity, each contains the seed of its opposite.

In bringing this largely Daoist terminology into Confucian discourse (chaos was generally frowned upon by Confucians), Zhou may have been attempting to show that the Confucian view of humanity’s role in the cosmos was not really opposed to the fundamentals of the Daoist worldview, in which human categories and values were thought to alienate human beings from the Dao. In effect, he was co-opting Daoist terminology to show that the Confucian worldview was actually more inclusive than the Daoist: it could accept a primordial chaos while still affirming the reality of the differentiated, phenomenal world. For Zhu Xi and his school, the most important contribution of this text was its integration of metaphysics (taiji, which Zhu equated with li, the ultimate natural/moral order) and cosmology (yin-yang and Five Phases).

Luc Paquin