Friend

Friend

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Weapons Training

Most Chinese styles also make use of training in the broad arsenal of Chinese weapons for conditioning the body as well as coordination and strategy drills. Weapons training (qìxiè) are generally carried out after the student is proficient in the basics, forms and applications training. The basic theory for weapons training is to consider the weapon as an extension of the body. It has the same requirements for footwork and body coordination as the basics. The process of weapon training proceeds with forms, forms with partners and then applications. Most systems have training methods for each of the Eighteen Arms of Wushu (shíbabanbingqì) in addition to specialized instruments specific to the system.

Application

Application refers to the practical use of combative techniques. Chinese martial arts techniques are ideally based on efficiency and effectiveness. Application includes non-compliant drills, such as Pushing Hands in many internal martial arts, and sparring, which occurs within a variety of contact levels and rule sets.

When and how applications are taught varies from style to style. Today, many styles begin to teach new students by focusing on exercises in which each student knows a prescribed range of combat and technique to drill on. These drills are often semi-compliant, meaning one student does not offer active resistance to a technique, in order to allow its demonstrative, clean execution. In more resisting drills, fewer rules apply, and students practice how to react and respond. ‘Sparring’ refers to the most important aspect of application training, which simulates a combat situation while including rules that reduce the chance of serious injury.

Competitive sparring disciplines include Chinese kickboxing Sanshou and Chinese folk wrestling Shuaijiao, which were traditionally contested on a raised platform arena Lèitái. Lèitái represents public challenge matches that first appeared in the Song Dynasty. The objective for those contests was to knock the opponent from a raised platform by any means necessary. San Shou represents the modern development of Lei Tai contests, but with rules in place to reduce the chance of serious injury. Many Chinese martial art schools teach or work within the rule sets of Sanshou, working to incorporate the movements, characteristics, and theory of their style. Chinese martial artists also compete in non-Chinese or mixed Combat sport, including boxing, kickboxing and Mixed martial arts.

Luc Paquin

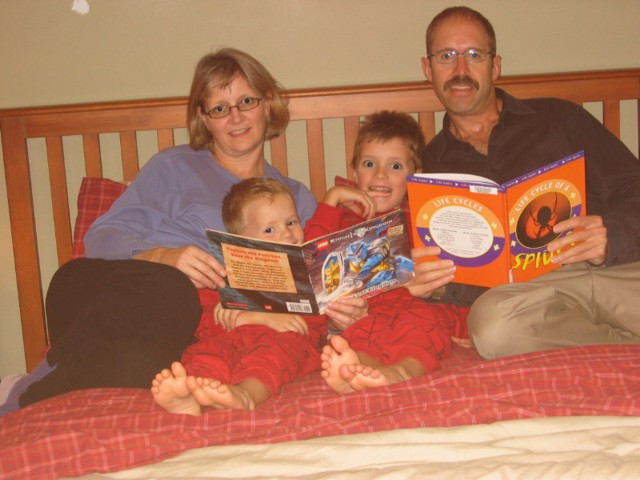

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys.

The Ardiel family piles into their big bed for a favourite nightly ritual. Jane reads a storybook aloud to her boys and husband while running her index finger along the page under the words so six-year old Ben can follow along. Sometimes Ben reads a page. Aiden, at four-years old is too young to read so he snuggles in to enjoy the tale. For dad Scott, although reading a sentence aloud is a struggle, he participates as fully as he can in this bonding family routine.

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys. “[Aphasia] , that’s been a struggle from the beginning. [I] can’t tell [the boys how to do things], but I have to show them,” says Scott.

Even though Scott knows what he wants to say, he has difficulty expressing it. Sometimes he finds it hard to understand what others are saying and reading can be difficult. Scott and Jane found the Aphasia Institute to be a “nugget of hope” once Scott was released from rehab after his stroke. They found comfort in an environment that understood the impact aphasia had on the whole family.

Jane joined the Family Support and Education Group and found a community that empathized with her experience.

Today Scott is a member of the Toastmaster Aphasia Gavel Club and an active volunteer at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. Jane has made it her mission to educate every medical professional they have encountered along this journey about aphasia.

“Much of my own healing through this experience has come from the opportunity to help others. There’s a saying – we achieve happiness when we seek the happiness and wellbeing of others,” says Jane.

Jane & Scott Ardiel

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Chinese martial arts training consists of the following components: basics, forms, applications and weapons; different styles place varying emphasis on each component. In addition, philosophy, ethics and even medical practice are highly regarded by most Chinese martial arts. A complete training system should also provide insight into Chinese attitudes and culture.

Basics

The Basics are a vital part of any martial training, as a student cannot progress to the more advanced stages without them. Basics are usually made up of rudimentary techniques, conditioning exercises, including stances. Basic training may involve simple movements that are performed repeatedly; other examples of basic training are stretching, meditation, striking, throwing, or jumping. Without strong and flexible muscles, management of Qi or breath, and proper body mechanics, it is impossible for a student to progress in the Chinese martial arts. A common saying concerning basic training in Chinese martial arts is as follows:

Train Both Internal and External

External training includes the hands, the eyes, the body and stances. Internal training includes the heart, the spirit, the mind, breathing and strength.

Stances

Stances (steps) are structural postures employed in Chinese martial arts training. They represent the foundation and the form of a fighter’s base. Each style has different names and variations for each stance. Stances may be differentiated by foot position, weight distribution, body alignment, etc. Stance training can be practiced statically, the goal of which is to maintain the structure of the stance through a set time period, or dynamically, in which case a series of movements is performed repeatedly. The Horse stance (qí ma bù/ma bù) and the bow stance are examples of stances found in many styles of Chinese martial arts.

Meditation

In many Chinese martial arts, meditation is considered to be an important component of basic training. Meditation can be used to develop focus, mental clarity and can act as a basis for qigong training.

Use of Qi

The concept of qi or ch’i is encountered in a number of Chinese martial arts. Qi is variously defined as an inner energy or “life force” that is said to animate living beings; as a term for proper skeletal alignment and efficient use of musculature (sometimes also known as fa jin or jin); or as a shorthand for concepts that the martial arts student might not yet be ready to understand in full. These meanings are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The existence of qi as a measurable form of energy as discussed in traditional Chinese medicine has no basis in the scientific understanding of physics, medicine, biology or human physiology.

There are many ideas regarding the control of one’s qi energy to such an extent that it can be used for healing oneself or others. Some styles believe in focusing qi into a single point when attacking and aim at specific areas of the human body. Such techniques are known as dim mak and have principles that are similar to acupressure.

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Styles

China has a long history of martial arts traditions that includes hundreds of different styles. Over the past two thousand years many distinctive styles have been developed, each with its own set of techniques and ideas. There are also common themes to the different styles, which are often classified by “families” (jia), “sects” (pai) or “schools” (men). There are styles that mimic movements from animals and others that gather inspiration from various Chinese philosophies, myths and legends. Some styles put most of their focus into the harnessing of qi, while others concentrate on competition.

Chinese martial arts can be split into various categories to differentiate them: For example, external and internal. Chinese martial arts can also be categorized by location, as in northern and southern as well, referring to what part of China the styles originated from, separated by the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang); Chinese martial arts may even be classified according to their province or city. The main perceived difference between northern and southern styles is that the northern styles tend to emphasize fast and powerful kicks, high jumps and generally fluid and rapid movement, while the southern styles focus more on strong arm and hand techniques, and stable, immovable stances and fast footwork. Examples of the northern styles include changquan and xingyiquan. Examples of the southern styles include Bak Mei, Wuzuquan, Choy Li Fut and Wing Chun. Chinese martial arts can also be divided according to religion, imitative-styles, and family styles such as Hung Gar. There are distinctive differences in the training between different groups of the Chinese martial arts regardless of the type of classification. However, few experienced martial artists make a clear distinction between internal and external styles, or subscribe to the idea of northern systems being predominantly kick-based and southern systems relying more heavily on upper-body techniques. Most styles contain both hard and soft elements, regardless of their internal nomenclature. Analyzing the difference in accordance with yin and yang principles, philosophers would assert that the absence of either one would render the practitioner’s skills unbalanced or deficient, as yin and yang alone are each only half of a whole. If such differences did once exist, they have since been blurred.

Luc Paquin

When people lose their ability to communicate due to brain damage caused by stroke or trauma, as persons with aphasia do, there is a good news and a bad news. The good news is that often not all is lost. Depending on the extensiveness of the damage, parts of the brain that used to be involved in speaking or understanding language may still be functioning. Speech therapies aim to induce these preserved areas to reorganize and regain their ability to produce and process speech. The not so good news is that such reorganization takes a long time, especially in older individuals.

Many people are familiar with traditional speech therapies that employ exercises to help persons with aphasia re-learn how to use language to communicate with their families and friends. Depending on the size and the location of brain damage, speech therapies can take years and improvement is usually slow. However, scientists are now looking into a newer type of treatment that combines traditional speech therapy with a weak electrical stimulation of the brain that might speed up recovery from aphasia. The method is called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and is applied non-invasively, by placing an electrode on top of the skull.

When people hear about electrical stimulation used to treat brain disorders, many conjure up an image from the 1975 movie “One flew over the cuckoo’s nest” which featured scenes of painful electroconvulsive therapy. This type of intervention, which in reality is painless, is still applied as a last resort to alleviate treatment-resistent depression and involves much stronger electrical currents than tDCS, which uses electrical current equivalent roughly to a 9V battery. The PBS Newshour video below describes the principles behind tDCS and how it could be applied for purposes like focusing the mind and keeping it alert.

The idea behind using tDCS in Aphasia therapy is that the small amount of current applied to the brain may enhance plasticity and prime the brain to learn faster. The approach would be to employ tDCS in combination with traditional clinical therapies rather than as a substitution.

There are many parts of the brain that are involved in understanding or producing speech and those parts are intricately connected into complex networks. Information flows between the various parts of the speech and language networks along cables called axons. Such information flow is important for the brain to access vocabulary and grammar rules, assemble words into sentences and send commands to the mouth and the tongue to produce speech. When stroke or trauma damages the areas that are part of this language network, the information flow is disturbed or cut off and people experience communication deficits. New connections need to be established between the preserved brain areas in order to regain one’s ability to speak.

The weak electrical currents of tDCS might stimulate the brain to form these new connections faster than it would with traditional speech therapy alone. But how exactly that would happen and what biological changes in the brain accompany the behavioral modulations observed in the video above is still unclear.

At present, tDCS as applied to aphasia is still considered experimental treatment and health insurance would not cover the cost of therapy. Data on tDCS efficacy for treating aphasia are still scarce. Most studies are conducted with small number of patients, limited language tasks, and short follow-up periods. However, at least some of the studies seem to suggest that tDCS has potential to improve aphasia rehabilitation.

Multiple centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe are in the process of conducting more rigorous clinical trials and may have more evidence soon whether tDCS works for aphasia. Those interested in enrolling in such studies can go to ClinicalTrials.gov to find out more information.

As methods improve and more data become available, tDCS may prove to be a great tool that will boost recovery from aphasia, which for the moment is still a long and arduous journey.

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Modern History

People’s Republic

Chinese martial arts experienced rapid international dissemination with the end of the Chinese Civil War and the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Many well known martial artists chose to escape from the PRC’s rule and migrate to Taiwan, Hong Kong, and other parts of the world. Those masters started to teach within the overseas Chinese communities but eventually they expanded their teachings to include people from other ethnic groups.

Within China, the practice of traditional martial arts was discouraged during the turbulent years of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1969-1976). Like many other aspects of traditional Chinese life, martial arts were subjected to a radical transformation by the People’s Republic of China to align them with Maoist revolutionary doctrine. The PRC promoted the committee-regulated sport of Wushu as a replacement for independent schools of martial arts. This new competition sport was disassociated from what was seen as the potentially subversive self-defense aspects and family lineages of Chinese martial arts.

In 1958, the government established the All-China Wushu Association as an umbrella organization to regulate martial arts training. The Chinese State Commission for Physical Culture and Sports took the lead in creating standardized forms for most of the major arts. During this period, a national Wushu system that included standard forms, teaching curriculum, and instructor grading was established. Wushu was introduced at both the high school and university level. The suppression of traditional teaching was relaxed during the Era of Reconstruction (1976-1989), as Communist ideology became more accommodating to alternative viewpoints. In 1979, the State Commission for Physical Culture and Sports created a special task force to reevaluate the teaching and practice of Wushu. In 1986, the Chinese National Research Institute of Wushu was established as the central authority for the research and administration of Wushu activities in the People’s Republic of China.

Changing government policies and attitudes towards sports in general led to the closing of the State Sports Commission (the central sports authority) in 1998. This closure is viewed as an attempt to partially de-politicize organized sports and move Chinese sport policies towards a more market-driven approach. As a result of these changing sociological factors within China, both traditional styles and modern Wushu approaches are being promoted by the Chinese government.

Chinese martial arts are an integral element of 20th-century Chinese popular culture. Wuxia or “martial arts fiction” is a popular genre that emerged in the early 20th century and peaked in popularity during the 1960s to 1980s. Wuxia films were produced from the 1920s. The Kuomintang suppressed wuxia, accusing it of promoting superstition and violent anarchy. Because of this, wuxia came to flourish in British Hong Kong, and the genre of kung fu movie in Hong Kong action cinema became wildly popular, coming to international attention from the 1970s. The genre declined somewhat during the 1980s, and in the late 1980s the Hong Kong film industry underwent a drastic decline, even before Hong Kong was handed to the People’s Republic in 1997. In the wake of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), there has been somewhat of a revival of Chinese-produced wuxia films aimed at an international audience, including Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004) and Reign of Assassins (2010).

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Modern History

Republican Period

Most fighting styles that are being practiced as traditional Chinese martial arts today reached their popularity within the 20th century. Some of these include Baguazhang, Drunken Boxing, Eagle Claw, Five Animals, Xingyi, Hung Gar, Monkey, Bak Mei Pai, Praying Mantis, Fujian White Crane, Jow Ga, Wing Chun and Taijiquan. The increase in the popularity of those styles is a result of the dramatic changes occurring within the Chinese society.

In 1900-01, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists rose against foreign occupiers and Christian missionaries in China. This uprising is known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion due to the martial arts and calisthenics practiced by the rebels. Empress Dowager Cixi gained control of the rebellion and tried to use it against the foreign powers. The failure of the rebellion led ten years later to the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the creation of the Chinese Republic.

The present view of Chinese martial arts are strongly influenced by the events of the Republican Period (1912-1949). In the transition period between the fall of the Qing Dynasty as well as the turmoil of the Japanese invasion and the Chinese Civil War, Chinese martial arts became more accessible to the general public as many martial artists were encouraged to openly teach their art. At that time, some considered martial arts as a means to promote national pride and build a strong nation. As a result, many training manuals were published, a training academy was created, two national examinations were organized as well as demonstration teams travelled overseas, and numerous martial arts associations were formed throughout China and in various overseas Chinese communities. The Central Guoshu Academy (Zhongyang Guoshuguan) established by the National Government in 1928 and the Jing Wu Athletic Association founded by Huo Yuanjia in 1910 are examples of organizations that promoted a systematic approach for training in Chinese martial arts. A series of provincial and national competitions were organized by the Republican government starting in 1932 to promote Chinese martial arts. In 1936, at the 11th Olympic Games in Berlin, a group of Chinese martial artists demonstrated their art to an international audience for the first time.

The term Kuoshu (or Guoshu, meaning “national art”), rather than the colloquial term gongfu was introduced by the Kuomintang in an effort to more closely associate Chinese martial arts with national pride rather than individual accomplishment.

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Shaolin and Temple-Based Martial Arts

The Shaolin style of kung fu is regarded as one of the first institutionalized Chinese martial arts. The oldest evidence of Shaolin participation in combat is a stele from 728 CE that attests to two occasions: a defense of the Shaolin Monastery from bandits around 610 CE, and their subsequent role in the defeat of Wang Shichong at the Battle of Hulao in 621 CE. From the 8th to the 15th centuries, there are no extant documents that provide evidence of Shaolin participation in combat.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, at least forty sources exist to provide evidence both that monks of Shaolin practiced martial arts, and that martial practice became an integral element of Shaolin monastic life. The earliest appearance of the frequently cited legend concerning Bodhidharma’s supposed foundation of Shaolin Kung Fu dates to this period. The origin of this legend has been traced to the Ming period’s Yijin Jing or “Muscle Change Classic”, a text written in 1624 attributed to Bodhidharma.

References of martial arts practice in Shaolin appear in various literary genres of the late Ming: the epitaphs of Shaolin warrior monks, martial-arts manuals, military encyclopedias, historical writings, travelogues, fiction and poetry. However these sources do not point out to any specific style originated in Shaolin. These sources, in contrast to those from the Tang period, refer to Shaolin methods of armed combat. These include a skill for which Shaolin monks became famous: the staff (gùn, Cantonese gwan). The Ming General Qi Jiguang included description of Shaolin Quan Fa (Wade-Giles: Shao Lin Ch’üan Fa; literally: “Shaolin fist technique”; Japanese: Shorin Kempo) and staff techniques in his book, Ji Xiao Xin Shu, which can translate as New Book Recording Effective Techniques. When this book spread to East Asia, it had a great influence on the development of martial arts in regions such as Okinawa and Korea.

Luc Paquin

Sacks on TED

Oliver Sacks

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Early History

The earliest references to Chinese martial arts are found in the Spring and Autumn Annals (5th century BCE), where a hand-to-hand combat theory, one that integrates notions of “hard” and “soft” techniques, is mentioned. A combat wrestling system called juélì or jiaolì is mentioned in the Classic of Rites. This combat system included techniques such as strikes, throws, joint manipulation, and pressure point attacks. Jiao Di became a sport during the Qin Dynasty (221-207 BCE). The Han History Bibliographies record that, by the Former Han (206 BCE – 8 CE), there was a distinction between no-holds-barred weaponless fighting, which it calls shoubó , for which training manuals had already been written, and sportive wrestling, then known as juélì. Wrestling is also documented in the Shi Jì, Records of the Grand Historian, written by Sima Qian (ca. 100 BCE).

In the Tang Dynasty, descriptions of sword dances were immortalized in poems by Li Bai. In the Song and Yuan dynasties, xiangpu contests were sponsored by the imperial courts. The modern concepts of wushu were fully developed by the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Philosophical Influences

The ideas associated with Chinese martial arts changed with the evolution of Chinese society and over time acquired some philosophical bases: Passages in the Zhuangzi, a Daoist text, pertain to the psychology and practice of martial arts. Zhuangzi, its eponymous author, is believed to have lived in the 4th century BCE. The Dao De Jing, often credited to Lao Zi, is another Taoist text that contains principles applicable to martial arts. According to one of the classic texts of Confucianism, Zhou Li, Archery and charioteering were part of the “six arts” (Pinyin: liu yi, including rites, music, calligraphy and mathematics) of the Zhou Dynasty (1122-256 BCE). The Art of War, written during the 6th century BCE by Sun Tzu, deals directly with military warfare but contains ideas that are used in the Chinese martial arts.

Daoist practitioners have been practicing Tao Yin (physical exercises similar to Qigong that was one of the progenitors to T’ai chi ch’uan) from as early as 500 BCE. In 39-92 CE, “Six Chapters of Hand Fighting”, were included in the Han Shu (history of the Former Han Dynasty) written by Pan Ku. Also, the noted physician, Hua Tuo, composed the “Five Animals Play” – tiger, deer, monkey, bear, and bird, around 220 CE. Daoist philosophy and their approach to health and exercise have influenced the Chinese martial arts to a certain extent. Direct reference to Daoist concepts can be found in such styles as the “Eight Immortals,” which uses fighting techniques attributed to the characteristics of each immortal.

Luc Paquin