Spirituality

Spirituality

Joseph A. Adler

Penetrating the Classic of Change (Tongshu)

The Tongshu, in forty sections, focuses on the Sage as the model of humanity. Here Zhou Dunyi defines Sagehood in terms of “authenticity” (cheng), a term found prominently in the classical Confucian text, The Mean (Zhongyong). To be authentic is to be true to the innate goodness of one’s nature; to actualize one’s moral potential. Zhou defines authenticity in cosmological terms taken from the appendices to the Classic of Change (Yijing). In this way he uses the concept of authenticity to link cosmology and Confucian ethics. There is significant overlap between the Tongshu and theTaijitu shuo (above), especially in their discussions of activity and stillness as the basic expressions of yang and yin. But the Tongshu is less metaphysical; the emphasis here is on the moral psychology of the Sage.

1. Being authentic (cheng)

- Being authentic is the foundation of the Sage. “Great indeed is the originating [power] of Qian! The myriad things rely on it for their beginnings.” It is the source of being authentic. “The way of Qian is transformation, with each [thing] receiving its correct nature and endowment.” In this way authenticity is established. Being pure and flawless, it is perfectly good. Thus: “The alternation of yin and yang is called the Way. That which issues from it is good. That which fulfills it is human nature.” “Origination and development” are the penetration of authenticity; “adaptation and correctness” are the recovery of authenticity. Great indeed is change (yi)! It is the source of human nature and endowment.

2. Being authentic (cheng)

- Being a Sage is nothing more than being authentic. Being authentic is the foundation of the Five Constant [Virtues] and the source of the Hundred Practices. It is imperceptible when [one is] still, and perceptible when [one is] active; perfectly correct [in stillness] and clearly pervading [in activity]. When the Five Constants and Hundred Practices are not authentic, they are wrong; blocked by depravity and confusion.

- Therefore one who is authentic has no [need for] undertakings (shi). It is perfectly easy, yet difficult to practice; when one is determined and precise, there is no difficulty with it. Therefore [Confucius said], “If in one day one could subdue the self and return to ritual decorum, then all under Heaven would recover their humanity.”

3. Authenticity, Incipience, and Virtue (cheng ji de)

- In being authentic there is no deliberate action (wuwei). In incipience (ji) there is good and evil. As for the [Five Constant] Virtues, loving is called humaneness (ren), being right is called appropriateness (yi), being principled (li) is called ritual decorum (li), being penetrating is called wisdom (zhi), and preserving is called trustworthiness (hsin). One who is by nature like this, at ease like this, is called a Sage. One who recovers it and holds onto it is called a Worthy. One whose subtle signs of expression are imperceptible, and whose fullness is inexhaustible, is called Spiritual (shen).

4. Sagehood (sheng)

- That which is “completely silent and inactive” is authenticity. That which “penetrates when stimulated” is spirit (shen). That which is active but not yet formed, between existing and not existing, is incipient. Authenticity is of the essence (jing), and therefore clear. Spirit is responsive, and therefore mysterious. Incipience is subtle, and therefore obscure. One who is authentic, spiritual, and incipient is called a Sage.

5. Activity and Stillness (dong jing)

- Activity as the absence of stillness and stillness as the absence of activity characterize things (wu). Activity that is not [empirically] active and stillness that is not [empirically] still characterize spirit (shen). Being active and yet not active, still and yet not still, does not mean that [spirit] is neither active nor still. For while things do not [inter-]penetrate (tong), spirit subtly [penetrates/pervades] the myriad things.

- The yin of water is based in yang; the yang of fire is based in yin. The Five Phases are yin and yang; yin and yang are the Supreme Polarity. The Four Seasons revolve; the myriad things end and begin [again]. How undifferentiated! How extensive! And how inexhaustible!

6. Learning to be a Sage (sheng xue)

- [Someone asked:] “Can Sagehood be learned?” Reply: It can. “Are there essentials (yao)?” Reply: There are. “I beg to hear them.” Reply: To be unified (yi) is essential. To be unified is to have no desire. Without desire one is vacuous when still and direct in activity. Being vacuous when still, one will be clear (ming); being clear one will be penetrating (tong). Being direct in activity one will be impartial (gong); being impartial one will be all-embracing (pu). Being clear and penetrating, impartial and all-embracing, one is almost [a Sage].

Luc Paquin

Joseph A. Adler

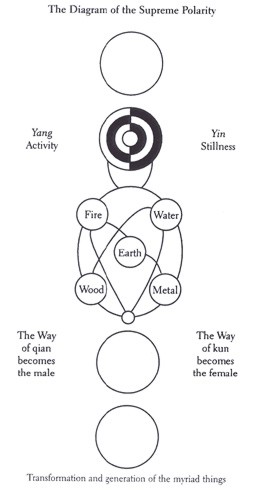

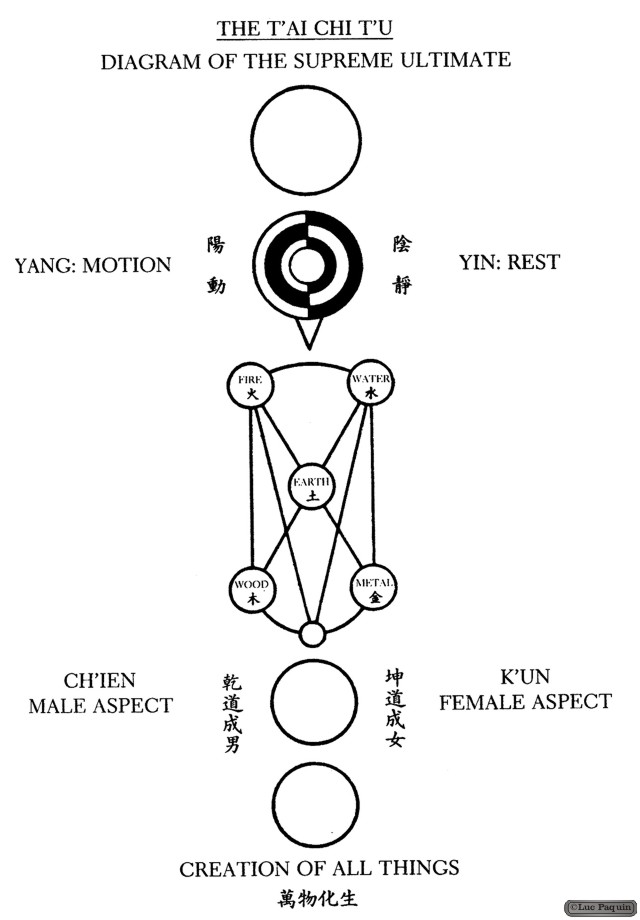

“Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taiji tu)

“Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taijitu shuo)

- Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)! The Supreme Polarity in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established.

- The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.

- The reality of the Non-polar and the essence of the Two [Modes] and Five [Phases] mysteriously combine and coalesce. “The Way of Qian becomes the male; the Way of Kun becomes the female;” the two qi stimulate each other, transforming and generating the myriad things. The myriad things generate and regenerate, alternating and transforming without end.

- Only humans receive the finest and most spiritually efficacious [qi]. Once formed, they are born; when spirit (shen) is manifested, they have intelligence; when their five-fold natures are stimulated into activity, good and evil are distinguished and the myriad affairs ensue.

- The Sage settles these [affairs] with centrality, correctness, humaneness and rightness (the Way of the Sage is simply humaneness, rightness, centrality and correctness) and emphasizes stillness. (Without desire, [he is] therefore still.) In so doing he establishes the ultimate of humanity. Thus the Sage’s “virtue equals that of Heaven and Earth; his clarity equals that of the sun and moon; his timeliness equals that of the four seasons; his good fortune and bad fortune equal those of ghosts and spirits.” The superior person cultivates these and has good fortune. The inferior person rejects these and has bad fortune.

- Therefore [the Classic of Change says], “Establishing the Way of Heaven, [the Sages] speak of yin and yang; establishing the Way of Earth they speak of yielding and firm [hexagram lines]; establishing the Way of Humanity they speak of humaneness and rightness.” It also says, “[The Sage] investigates beginnings and follows them to their ends; therefore he understands death and birth.” Great indeed is [the Classic of] Change! Herein lies its perfection.

Luc Paquin

Joseph A. Adler

Diagram of the Supreme Polarity (Taiji tu)

Zhou’s best-known contribution to the Neo-Confucian tradition was his brief “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” and the Diagram itself. The text has engendered controversy and debate ever since the twelfth century, when Zhu Xi and Lü Zuqian (1137-1181) placed it at the head of their Neo-Confucian anthology, Reflections on Things at Hand (Jinsilu), in 1175. It was controversial from a sectarian Confucian standpoint because the diagram explained by the text was attributed to a prominent Daoist master, Chen Tuan (Chen Xiyi, 906-989), and because the key terms of the text had well-known Daoist origins. Scholars to the present day have attempted to interpret what Zhou Dunyi meant by them.

The two key terms, which appear in the opening line of the Explanation, are wuji and taiji, translated here as “Non-Polar” and “Supreme Polarity.” Wuji had been used in the classical Daoist texts, Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Liezi. Wu is a negation, roughly equivalent to “there is not;” ji is literally the ridgepole of a peaked roof, and usually means “limit” or “ultimate.” So in these early texts wuji means “the unlimited,” or “the infinite.” But in later Daoist texts it came to denote a state of primordial chaos, prior to the differentiation of yin and yang, and sometimes equivalent to dao.

Taiji was found in several classical texts, mostly but not exclusively Daoist. For the Song Neo-Confucians, the locus classicus of taiji was the Appended Remarks (Xici), or Great Treatise (Dazhuan), one of the appendices of the Classic of Change (Yijing): “In change there is the Supreme Polarity, which generates the Two Modes [yin and yang]”. Taiji here is a generative principle of bipolarity.

But the term was much more prominent and nuanced in Daoism than in Confucianism. Taiji was the name of one of the Daoist heavens, and thus was prefixed to the names of many Daoist immortals, or divinities, and to the titles of the texts attributed to them. It was sometimes identified with Taiyi, the Supreme One (a Daoist divinity), and with the pole star of the Northern Dipper. It carried connotations of a turning point in a cycle, an end point before a reversal, and a pivot between bipolar processes. It became a standard part of Daoist cosmogonic schemes, where it usually denoted a stage of chaos later than wuji, a stage or state in which yin and yang have differentiated but have not yet become manifest. It thus represented a “complex unity,” or the unity of potential multiplicity. In the form of Daoist meditation known as neidan, or physiological alchemy, it represented the energetic potential to reverse the normal process of aging by cultivating within one’s body the spark of the primordial qi (psycho-physical substance), thereby “returning” to the primordial, creative state of chaos from which the cosmos evolved. Chen Tuan’s Taiji Diagram, when read from the bottom upwards, is thought to have been originally a schematic representation of this process of “returning to wuji”, the “Non-Polar,” undifferentiated state.

Zhou Dunyi ignored the bottom-up reading of the Diagram, leaving one or two of its elements unexplained. Focusing on the top-down differentiation of the cosmos from the primordial unity to the “myriad things,” he departed from a Daoist interpretation by singling out the human being as the highest manifestation of cosmic creativity, thereby giving the Diagram a distinctly Confucian meaning. The enigmatic opening line of his Explanation suggests that the Supreme Polarity, the ultimate principle of differentiation, is itself fundamentally undifferentiated (this is stated explicitly a few sentences later). Similarly, activity and stillness, the first manifestations of polarity, each contains the seed of its opposite.

In bringing this largely Daoist terminology into Confucian discourse (chaos was generally frowned upon by Confucians), Zhou may have been attempting to show that the Confucian view of humanity’s role in the cosmos was not really opposed to the fundamentals of the Daoist worldview, in which human categories and values were thought to alienate human beings from the Dao. In effect, he was co-opting Daoist terminology to show that the Confucian worldview was actually more inclusive than the Daoist: it could accept a primordial chaos while still affirming the reality of the differentiated, phenomenal world. For Zhu Xi and his school, the most important contribution of this text was its integration of metaphysics (taiji, which Zhu equated with li, the ultimate natural/moral order) and cosmology (yin-yang and Five Phases).

Luc Paquin

Joseph A. Adler

Zhou Dunyi (or Zhou Lianxi, 1017-1073) occupies a position in the Chinese tradition based on a role assigned to him by Zhu Xi (1130-1200), the architect of the Neo-Confucian school that eventually became “orthodox.” According to one version of the Succession to the Way (daotong) given by Zhu Xi, Zhou was the first true Confucian Sage since Mencius (4th c. BCE), and was a formative influence on Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi (Zhou’s nephews), from whom Zhu Xi drew significant parts of his system of thought and practice. Thus Zhou Dunyi came to be known as the “founding ancestor” of the Cheng-Zhu school, which dominated Chinese philosophy for over 700 years. His “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taijitu shuo), as interpreted by Zhu, became the accepted foundation of Neo-Confucian cosmology. Along with his other major work, Penetrating the Classic of Change (Tongshu), it established the appendices to the Yijing as basic textual sources of the Neo-Confucian revival of the Song dynasty. And Zhou’s short essay, “On the Love of the Lotus” (Ai lian shuo), is still a regular part of the high school curriculum in Taiwan.

Zhou was born to a family of scholar-officials in Hunan province. After his father died when he was about fourteen, he was adopted by his maternal uncle, Zheng Xiang, through whom he later obtained his first government post. Despite the increasing importance of the civil service examination system in determining status in Song society, Zhou never obtained the “Presented Scholar” (jinshi) degree. Consequently, while he earned praise for his service in a very active official career, he never rose to a high position.

Zhou’s honorific name, Lianxi (“Lian Stream”), was the one he gave to his study, built in 1062 at the foot of Mt. Lu in Jiangxi province; it was named after a stream in Zhou’s home village. He was posthumously honored in 1200 as Yuangong (Duke of Yuan), and in 1241 was accorded sacrifices in the official Confucian temple.

During his lifetime, Zhou was not an influential figure in Song political or intellectual life. He had few, if any, formal students other than his nephews, the Cheng brothers, who studied with him only briefly when they were teenagers. He was most remembered by his contemporaries for the evident quality of his personality and mind. He was known as a warm, humane man who felt a deep kinship with the natural world, a man with penetrating insight into the Way of Heaven, the natural-moral order. To later Confucians he personified the virtue of “authenticity” (cheng), the full realization of the innate goodness and wisdom of human nature.

Zhou’s connection with the Cheng brothers was the ostensible rationale for his being considered the founder of the Cheng-Zhu school of Neo-Confucianism. Yet that connection was, in fact, slight. Although they later spoke fondly of their short time with him and were personally impressed with him (as were many other contemporaries), the Chengs did not acknowledge any specific philosophical debts to Zhou. Nor are any such debts evident in their teachings. In fact, Zhou’s teachings were rather suspect in the eyes of many Song Confucians because of his evident debts to Daoism. This was especially true during the Southern Song (1127-1279), when Confucians increasingly defined themselves in opposition to Buddhism and Daoism. Indeed, Zhou’s “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” attracted considerable interest among Daoists, and made its way into the Daoist Canon (Daozang).

Given Zhou’s tenuous connection with the Chengs, why then did Zhu Xi regard him as the first Sage of the Song? The question is significant, for had it not been for Zhu Xi’s estimation of him, Zhou’s writings would almost certainly not have become as central to the Neo-Confucian tradition as they are. They apparently were not widely known outside the circle of the Chengs and their students until the twelfth century, and today the only extant editions besides those edited by Zhu Xi are the Taijitu shuo in the Daoist Canon and the Tongshu in another anthology , neither of which is accompanied by a commentary. So it is safe to say that Zhou Dunyi’s place in the Chinese tradition is largely a creation of Zhu Xi.

It was the content of Zhou’s teachings in relation to Zhu Xi’s system of thought and practice that persuaded Zhu to exalt Zhou Dunyi, to ignore his Daoist connections, and to stretch the available data concerning Zhou’s affiliation with the Chengs.[6] Zhu was particularly interested in the relationship between the active, functioning mind (xin) and its metaphysical substance or nature (xing), and in the implications of that relationship for moral self-cultivation. Zhou’s writings supported Zhu’s position on these issues by integrating the metaphysical, psycho-physical, and ethical dimensions of the mind, chiefly by means of the concepts of “Supreme Polarity” (taiji), “authenticity” (cheng), and the interpenetration of activity (dong) and stillness (jing).

Translated below are the complete text of his best-known work, the “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taijitu shuo) and six of the forty short sections of Penetrating the Classic of Change (Tongshu). These works stand on their own as foundational texts of the Neo-Confucian tradition and as superb examples of the integration of Confucian ethics and Daoist naturalism.

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts – Tai Chi – Taiji

Core Concept

Taiji is understood to be the highest conceivable principle, that from which existence flows. This is very similar to the Daoist idea “reversal is the movement of the Dao”. The “supreme ultimate” creates yang and yin: movement generates yang; when its activity reaches its limit, it becomes tranquil. Through tranquility the supreme ultimate generates yin. When tranquility has reached its limit, there is a return to movement. Movement and tranquility, in alternation, become each the source of the other. The distinction between the yin and yang is determined and the two forms (that is, the yin and yang) stand revealed. By the transformations of the yang and the union of the yin, the 5 elements (Qi) of water, fire, wood, metal and earth are produced. These 5 Qi become diffused, which creates harmony. Once there is harmony the 4 seasons can occur. Yin and yang produced all things, and these in their turn produce and reproduce, this makes these processes never ending. Taiji underlies the practical Taijiquan (T’ai Chi Ch’uan) – A Chinese internal martial art based on the principles of Yin and Yang and Taoist philosophy, and devoted to internal energetic and physical training. Taijiquan is represented by five family styles: Chen, Sun, Yang, Wu(Hao), and Wu.

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts – Tai Chi – Taiji

Taiji is a Chinese cosmological term for the “Supreme Ultimate” state of undifferentiated absolute and infinite potential, the oneness before duality, from which Yin and Yang originate, contrasted with the Wuji (“Without Ultimate”).

The term Taiji and its other spelling T’ai chi (using Wade-Giles as opposed to Pinyin) are most commonly used in the West to refer to Taijiquan (or T’ai chi ch’uan), an internal martial art, Chinese meditation system and health practice. This article, however, refers only to the use of the term in Chinese philosophy and Taoist spirituality.

Taiji in Chinese Texts

Taiji references are found in Chinese classic texts associated with many schools of Chinese philosophy.

Zhang and Ryden explain the ontological necessity of Taiji.

- Any philosophy that asserts two elements such as the yin-yang of Chinese philosophy will also look for a term to reconcile the two, to ensure that both belong to the same sphere of discourse. The term ‘supreme ultimate’ performs this role in the philosophy of the Book of Changes. In the Song dynasty it became a metaphysical term on a par with the Way.

Zhuangzi

The Daoist classic Zhuangzi introduced the Taiji concept. One of the (ca. 3rd century BCE) “Inner Chapters” contrasts Taiji “great ultimate” (“zenith”) and Liuji “six ultimates; six cardinal directions” (“nadir”).

- The Way has attributes and evidence, but it has no action and no form. It may be transmitted but cannot be received. It may be apprehended but cannot be seen. From the root, from the stock, before there was heaven or earth, for all eternity truly has it existed. It inspirits demons and gods, gives birth to heaven and earth. It lies above the zenith but is not high; it lies beneath the nadir but is not deep. It is prior to heaven and earth, but is not ancient; it is senior to high antiquity, but it is not old.

Huainanzi

The (2nd century BCE) Huainanzi mentions Taiji in a context of a Daoist Zhenren “true person; perfected person” who perceives from a “Supreme Ultimate” that transcends categories like yin and yang.

- The fu-sui (burning mirror) gathers fire energy from the sun; the fang-chu (moon mirror) gathers dew from the moon. What are [contained] between Heaven and Earth, even an expert calculator cannot compute their number. Thus, though the hand can handle and examine extremely small things, it cannot lay hold of the brightness [of the sun and moon]. Were it within the grasp of one’s hand (within one’s power) to gather [things within] one category from the Supreme Ultimate (t’ai-chi) above, one could immediately produce both fire and water. This is because Yin and Yang share a common ch’i and move each other.

I Ching

Taiji also appears in the Xìcí “Appended Judgments” commentary to the I Ching, a late section traditionally attributed to Confucius but more likely dating to about the 3rd century B.C.E.

- Therefore there is in the Changes the Great Primal Beginning. This generates the two primary forces. The two primary forces generate the four images. The four images generate the eight trigrams. The eight trigrams determine good fortune and misfortune. Good fortune and misfortune create the great field of action.

This two-squared generative sequence includes Taiji -> Yin and Yang (two polarities) -> Sixiang (Four Symbols) -> Bagua (eight trigrams).

Richard Wilhelm and Cary F. Baynes explain.

- The fundamental postulate is the “great primal beginning” of all that exists, t’ai chi – in its original meaning, the “ridgepole”. Later Indian philosophers devoted much thought to this idea of a primal beginning. A still earlier beginning, wu chi, was represented by the symbol of a circle. Under this conception, t’ai chi was represented by the circle divided into the light and the dark, yang and yin, Yin yang.svg. This symbol has also played a significant part in India and Europe. However, speculations of a Gnostic-dualistic character are foreign to the original thought of the I Ching; what it posits is simply the ridgepole, the line. With this line, which in itself represents oneness, duality comes into the world, for the line at the same time posits an above and a below, a right and left, front and back – in a word, the world of the opposites.

Taijitu Shuo

The Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073 CE) wrote the Taijitu shuo “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate”, which became the cornerstone of Neo-Confucianist cosmology. His brief text synthesized aspects of Chinese Buddhism and Daoism with metaphysical discussions in the I ching.

Zhou’s key terms Wuji and Taiji appear in the opening line, which Adler notes could also be translated “The Supreme Polarity that is Non-Polar!”.

- Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)! The Supreme Polarity in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established. The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.

Instead of usual Taiji translations “Supreme Ultimate” or “Supreme Pole”, Adler uses “Supreme Polarity” (see Robinet 1990) because Zhu Xi describes it as the alternating principle of yin and yang, and …

- insists that taiji is not a thing (hence “Supreme Pole” will not do). Thus, for both Zhou and Zhu, taiji is the yin-yang principle of bipolarity, which is the most fundamental ordering principle, the cosmic “first principle.” Wuji as “non-polar” follows from this.

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts – Tai Chi

T’ai Chi Ch’uan Today

In the last twenty years or so, t’ai chi ch’uan classes that purely emphasise health have become popular in hospitals, clinics, as well as community and senior centres. This has occurred as the baby boomers generation has aged and the art’s reputation as a low-stress training method for seniors has become better known.

As a result of this popularity, there has been some divergence between those that say they practice t’ai chi ch’uan primarily for self-defence, those that practice it for its aesthetic appeal, and those that are more interested in its benefits to physical and mental health. The wushu aspect is primarily for show; the forms taught for those purposes are designed to earn points in competition and are mostly unconcerned with either health maintenance or martial ability. More traditional stylists believe the two aspects of health and martial arts are equally necessary: the yin and yang of t’ai chi ch’uan. The t’ai chi ch’uan “family” schools, therefore, still present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students in studying the art.

Philosophy

The philosophy of t’ai chi ch’uan is that, if one uses hardness to resist violent force, then both sides are certainly to be injured at least to some degree. Such injury, according to t’ai chi ch’uan theory, is a natural consequence of meeting brute force with brute force. Instead, students are taught not to directly fight or resist an incoming force, but to meet it in softness and follow its motion while remaining in physical contact until the incoming force of attack exhausts itself or can be safely redirected, meeting yang with yin. When done correctly, this yin/yang or yang/yin balance in combat, or in a broader philosophical sense, is a primary goal of t’ai chi ch’uan training. Lao Tzu provided the archetype for this in the Tao Te Ching when he wrote, “The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong.”

Traditional schools also emphasize that one is expected to show wude (“martial virtue/heroism”), to protect the defenseless, and show mercy to one’s opponents.

Health

A 2011 overview of existing research on t’ai chi ch’uan’s health effects found evidence of medical benefit for preventing falls, mental health, and general health in elderly people. There wasn’t conclusive evidence for any of the other conditions researched, including Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, cancer and arthritis.

The practice of t’ai chi ch’uan is encouraged by the National Parkinson Foundation and Diabetes Australia.

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts – Tai Chi

Relation to Taiji Philosophy

In modern usage, the term t’ai chi / taiji (unless further qualified as in “taiji philosophy” or “taiji diagram”) is now commonly understood, both in the West and in mainland China, to refer to the martial art and exercise system. However, the term has its origins in Chinese philosophy. The word taiji translates to “great pole/goal” or “supreme ultimate”, and is believed to be a pivotal, spiraling, or coiling force that transforms the neutrality of wuji to a state of polarity depicted by the taijitu. T’ai chi / taiji is thus symbolically represented by a state between wuji and the polar “yin and yang”, not by the actual yin and yang symbol, as is frequently misinterpreted. The combination of the term taiji and quan (“fist”), produces the martial art’s name taijiquan or “taiji fist”, showing the close link and use of the taiji concept in the martial art. Taijiquan does not directly refer to the use of qi as is commonly assumed. The practice of taijiquan is meant to be in harmony with taiji philosophy, utilising and manipulating qi via taiji, to produce great effect with minimal effort.

The appropriateness of this more recent appellation is seen in the oldest literature preserved by these schools where the art is said to be a study of yin (receptive) and yang (active) principles, using terminology found in the Chinese classics, especially the I Ching and the Tao Te Ching.

History and Styles

There are five major styles of t’ai chi ch’uan, each named after the Chinese family from which it originated:

- Chen-style of Chen Wangting (1580-1660)

- Yang-style of Yang Lu-ch’an (1799-1872)

- Wu- or Wu (Hao)-style of Wu Yu-hsiang (1812-1880)

- Wu-style of Wu Ch’uan-yu (1834-1902) and his son Wu Chien-ch’uan (1870-1942)

- Sun-style of Sun Lu-t’ang (1861-1932)

The order of verifiable age is as listed above. The order of popularity (in terms of number of practitioners) is Yang, Wu, Chen, Sun, and Wu/Hao. The major family styles share much underlying theory, but differ in their approaches to training.

There are now dozens of new styles, hybrid styles, and offshoots of the main styles, but the five family schools are the groups recognized by the international community as being the orthodox styles. Other important styles are Zhaobao t’ai chi ch’uan, a close cousin of Chen-style, which has been newly recognized by Western practitioners as a distinct style, the Fu style, created by Fu Chen Sung, which evolved from Chen, Sun and Yang styles, and also incorporates movements from Baguazhang (Pa Kua Chang) and the Cheng-style of Cheng Man Ch’ing which is a simplification of the traditional Yang style.

The differences between the different styles range from varying speeds to the way in which the movements are performed. For example, the form “Parting the wild horse’s mane” in Yang-style does not at all resemble the very same movement in Sun-style. Also, the Sun 73 forms take as long to perform as the Yang 24 forms.

All existing styles can be traced back to the Chen-style, which had been passed down as a family secret for generations. The Chen family chronicles record Chen Wangting, of the family’s 9th generation, as the inventor of what is known today as t’ai chi ch’uan. Yang Luchan became the first person outside the family to learn t’ai chi ch’uan. His success in fighting earned him the nickname Yang Wudi, which means “Unbeatable Yang”, and his fame and efforts in teaching greatly contributed to the subsequent spreading of t’ai chi ch’uan knowledge.

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts – Tai Chi

Historic Origin

When tracing t’ai chi ch’uan’s formative influences to Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, there seems little more to go on than legendary tales from a modern historical perspective, but t’ai chi ch’uan’s practical connection to and dependence upon the theories of Sung dynasty Neo-Confucianism (a conscious synthesis of Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian traditions, especially the teachings of Mencius) is claimed by some traditional schools. T’ai chi ch’uan’s theories and practice are believed by these schools to have been formulated by the Taoist monk Zhang Sanfeng in the 12th century, at about the same time that the principles of the Neo-Confucian school were making themselves felt in Chinese intellectual life. However, modern research casts serious doubts on the validity of those claims, pointing out that a 17th-century piece called “Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan” (1669), composed by Huang Zongxi (1610-1695 A.D.), is the earliest reference indicating any connection between Zhang Sanfeng and martial arts whatsoever, and must not be taken literally but must be understood as a political metaphor instead. Claims of connections between t’ai chi ch’uan and Zhang Sanfeng appeared no earlier than the 19th century.

History records that Yang Luchan trained with the Chen family for 18 years before he started to teach the art in Beijing, which strongly suggests that his art was based on, or heavily influenced by, the Chen family art. The Chen family are able to trace the development of their art back to Chen Wangting in the 17th century.

What is now known as “t’ai chi ch’uan” appears to have received this appellation from only around the mid-1800s. There was a scholar in the Imperial Court by the name of Ong Tong He who witnessed a demonstration by Yang Luchan at a time before Yang had established his reputation as a teacher. Afterwards Ong wrote: “Hands holding Taiji shakes the whole world, a chest containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes.” Before this time the art may have had a number of different names, and appears to have been generically described by outsiders as zhan quan (“touch boxing”), mian quan (“soft boxing”) or shisan shi (“the thirteen techniques”).

Luc Paquin

Martial Arts – Tai Chi

Often shortened to t’ai chi, taiji or tai chi in English usage, T’ai chi ch’uan or tàijíquán is an internal Chinese martial art practiced for both its defense training and its health benefits. It is also typically practiced for a variety of other personal reasons: its hard and soft martial art technique, demonstration competitions, and longevity. As a result, a multitude of training forms exist, both traditional and modern, which correspond to those aims. Some training forms of t’ai chi ch’uan are especially known for being practiced with relatively slow movement.

Today, t’ai chi ch’uan has spread worldwide. Most modern styles of t’ai chi ch’uan trace their development to at least one of the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu, and Sun.

Overview

The term “t’ai chi ch’uan” translates as “supreme ultimate fist”, “grand supreme fist”, “boundless fist”, “supreme ultimate boxing” or “great extremes boxing”. The chi in this instance is the Wade-Giles transliteration of the Pinyin jí, and is distinct from qì (ch’i, “life energy”). The concept of the taiji (“supreme ultimate”), in contrast with wuji (“without ultimate”), appears in both Taoist and Confucian Chinese philosophy, where it represents the fusion or mother of Yin and Yang into a single ultimate, represented by the taijitu symbol Taijitu. T’ai chi ch’uan theory and practice evolved in agreement with many Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism.

T’ai chi ch’uan training involves five elements, taolu (solo hand and weapons routines/forms), neigong & qigong (breathing, movement and awareness exercises and meditation), tuishou (response drills) and sanshou (self defence techniques). While t’ai chi ch’uan is typified by some for its slow movements, many t’ai chi styles (including the three most popular – Yang, Wu, and Chen) – have secondary forms with faster pace. Some traditional schools of t’ai chi teach partner exercises known as tuishou (“pushing hands”), and martial applications of the taolu’s (forms’) postures.

In China, t’ai chi ch’uan is categorized under the Wudang grouping of Chinese martial arts – that is, the arts applied with internal power. Although the Wudang name falsely suggests these arts originated at the so-called Wudang Mountain, it is simply used to distinguish the skills, theories and applications of neijia (“internal arts”) from those of the Shaolin grouping, waijia (“hard” or “external”) martial art styles.

Since the first widespread promotion of t’ai chi ch’uan’s health benefits by Yang Shaohou, Yang Chengfu, Wu Chien-ch’uan, and Sun Lutang in the early 20th century, it has developed a worldwide following among people with little or no interest in martial training, for its benefit to health and health maintenance. Medical studies of t’ai chi support its effectiveness as an alternative exercise and a form of martial arts therapy.

It is purported that focusing the mind solely on the movements of the form helps to bring about a state of mental calm and clarity. Besides general health benefits and stress management attributed to t’ai chi ch’uan training, aspects of traditional Chinese medicine are taught to advanced t’ai chi ch’uan students in some traditional schools.

Some other forms of martial arts require students to wear a uniform during practice. In general, t’ai chi ch’uan schools do not require a uniform, but both traditional and modern teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.

The physical techniques of t’ai chi ch’uan are described in the “T’ai chi classics”, a set of writings by traditional masters, as being characterized by the use of leverage through the joints based on coordination and relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in order to neutralize, yield, or initiate attacks. The slow, repetitive work involved in the process of learning how that leverage is generated gently and measurably increases, opens the internal circulation (breath, body heat, blood, lymph, peristalsis, etc.).

The study of t’ai chi ch’uan primarily involves three aspects:

- Health: An unhealthy or otherwise uncomfortable person may find it difficult to meditate to a state of calmness or to use t’ai chi ch’uan as a martial art. T’ai chi ch’uan’s health training, therefore, concentrates on relieving the physical effects of stress on the body and mind. For those focused on t’ai chi ch’uan’s martial application, good physical fitness is an important step towards effective self-defense.

- Meditation: The focus and calmness cultivated by the meditative aspect of t’ai chi ch’uan is seen as necessary in maintaining optimum health (in the sense of relieving stress and maintaining homeostasis) and in application of the form as a soft style martial art.

- Martial Art: The ability to use t’ai chi ch’uan as a form of self-defense in combat is the test of a student’s understanding of the art. T’ai chi ch’uan is the study of appropriate change in response to outside forces, the study of yielding and “sticking” to an incoming attack rather than attempting to meet it with opposing force. The use of t’ai chi ch’uan as a martial art is quite challenging and requires a great deal of training.

Luc Paquin